https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LuXULbJmq1U

철기 시대 사카 문화의 유전적 특징

철기 시대 주목할 만한 유목 문명 주역 사카Saka는 광활한 유라시아 대초원에 지울 수 없는 흔적을 남겼다.

최근 고고학 및 유전학 연구를 통해 키르기스스탄 보즈-바르막 고분Boz-Barmak burial ground에서 광범위한 통찰력이 발견되었다.

이곳에는 목재와 돌로 둘러싸인 12구 유해가 묻혀 있으며, 기원전 4세기에서 기원전 2세기까지 이야기를 들려준다.

이러한 발견은 중앙 유라시아 중심부에서 번성한 이 고대 사회의 유전적 모자이크, 사회 구조, 그리고 문화적 복잡성을 엿볼 수 있는 매혹적인 기회를 제공한다.

보즈-바르막 고고학 발굴

보즈-바르막 산맥Boz-Barmak mountains 품에 숨은 이 고고학 유적은 키르기스스탄 발리크치Balykchi 마을 남동쪽, 신비로운 이식쿨 호수Issyk-Kul Lake 남서쪽 기슭에 자리 잡고 있다.

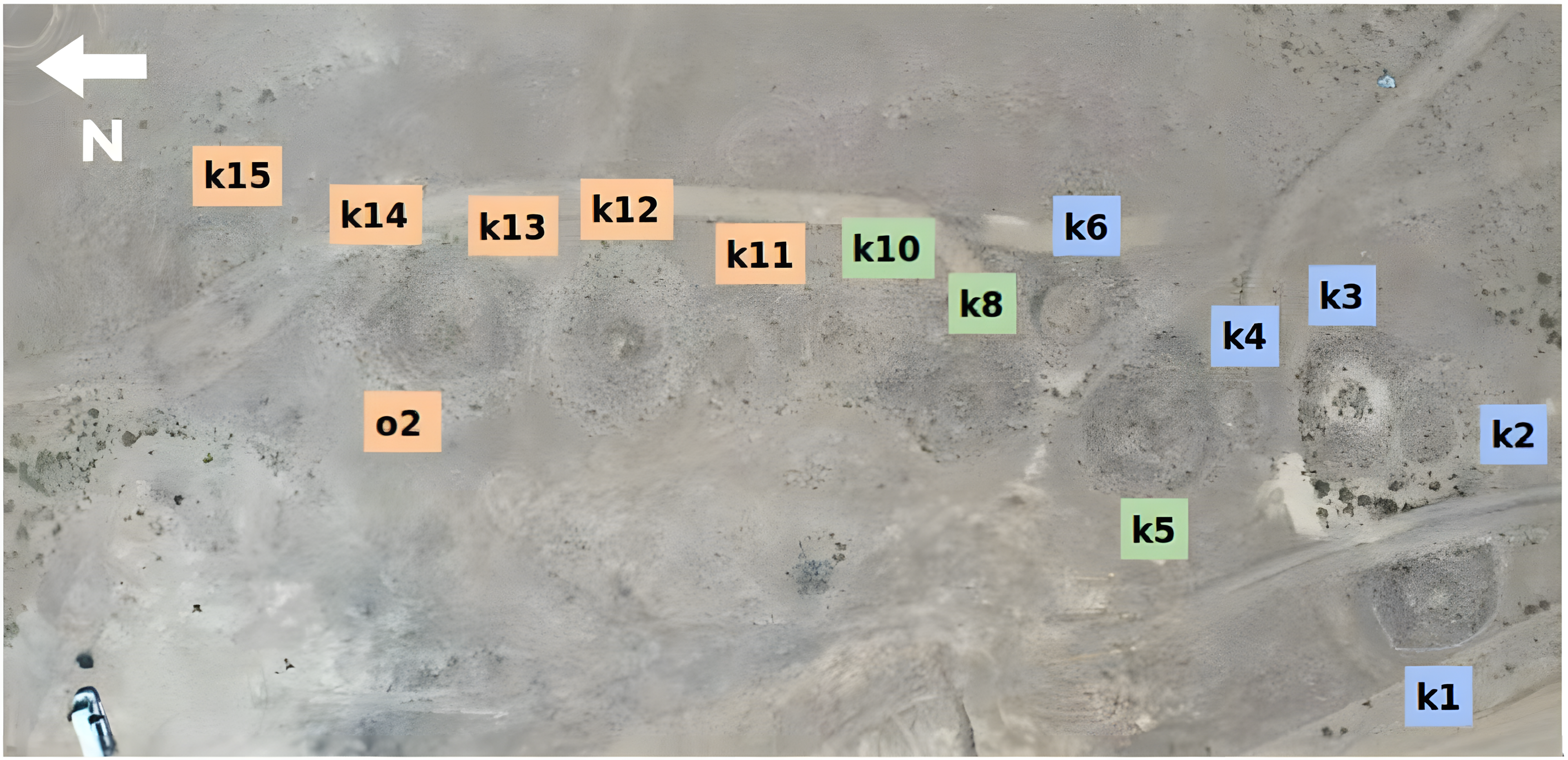

2022년 철도 공사로 인한 구조 발굴 과정에서 발견된 이 매장지는 남북으로 길게 뻗은 14개 무덤으로 구성되며, 고대 사카 엘리트층의 건축적 기량과 의례적 관습을 보여준다.

나무 골조와 점토로 봉분을 쌓고 돌로 고정한 이 매장 구조물은 정교한 장인 기술과 공동 노동 조직에 기반을 둔 사회를 반영한다.

쿠르간kurgan으로 알려진 이 매장지들은 상당한 규모 차이를 보이는데, 지름은 7~14미터, 높이는 약 1미터에 이른다.

이러한 차이는 사카 사회의 미묘한 사회적 위계 질서를 시사한다.

이 쿠르간들은 여러 겹 목재, 관목, 점토 블록으로 꼼꼼하게 건축되었으며, 이는 고인을 기리고 유해를 영원히 보존하기 위해 얼마나 세심한 주의를 기울였는지를 보여준다.

5, 8, 10, 11, 13번 쿠르간을 포함한 더 큰 구조물들은 그 웅장한 규모를 과시하며, 이는 당시 개인들이 얼마나 존경받는 지위를 누렸는지, 아마도 군사 지도자, 지역 사회의 든든한 인물, 또는 생전에 존경을 받은 영향력 있는 인물이었음을 보여준다.

부장품 및 문화 유물

이 고분에서 발견된 고고학적 유물들은 사카족의 물질 문화와 예술적 정교함을 생생하게 보여준다.

쿠르간 10은 이 중 가장 오래된 것으로 추정되며, 금으로 만든 마름모 모양 접시와 세잎무늬를 새긴 의례용 항아리와 같은 주목할 만한 유물들을 포함하고 있어 헬레니즘 이전 문화의 영향을 짐작하게 한다.

섬세한 금 귀걸이, 식물 무늬로 장식한 정교하게 제작된 뼈 버클, 청동 접이식 거울, 정교한 땋은 머리 장식과 함께 이러한 정교한 유물들은 사카족의 미적 세련미와 풍부한 문화적 유산을 보여준다.

아마도 가장 중요한 것은 부장품들이 사카 사회의 성 역학에 대한 흥미로운 통찰을 보여준다는 점이다.

보즈-바르막에 묻힌 여성들 무덤은 높은 지위를 보여주는 보석과 유물들로 장식되며, 이는 당시 군사와 정치 활동에 적극적으로 참여한 것으로 보인다.

예를 들어, 쿠르간 13호에서는 금반지 귀걸이와 기타 명망 있는 물품들과 함께 여성 유골이 발견되었는데, 이는 여성의 권위가 가부장적 전통과 함께, 때로는 가부장적 전통에도 불구하고 번성할 수 있는 공간을 지닌 사회였음을 시사한다.

이러한 증거는 고대 유목 사회의 성 역할에 대한 기존 가정에 도전하며, 이전에 알려진 것보다 훨씬 복잡한 사회 구조를 시사한다.

유전적 발견과 조상과의 연결

이 고대인들에 대한 최첨단 DNA 분석은 그들의 유전적 기원을 생생하게 그려내며, 고대 중앙 유라시아와 시베리아에 걸쳐 다양한 조상 집단과 이들을 연결한다.

9명 개체에 대한 정밀한 고대 DNA 추출 및 분석을 통해 연구진은 사카 공동체 내 연속성과 다양성을 모두 보여주는 매혹적인 유전적 지형을 발견했다.

특히 주목할 만한 점은 남성 혈통이 오늘날 키르기스족과 타지크족 인구와 놀라운 연속성을 보인다는 사실이다.

이는 수많은 역사적 격변과 인구 이동에도 수천 년 동안 지속한 유전적 특징을 추적하는 것이다.

유전적 모델링은 사카인들이 다양한 조상의 놀라운 융합을 구현한다는 점에서 세계적인 정체성을 보여준다.

그들의 유전적 구성에는 시베리아의 사르가트족Sargat people과 같은 스키타이 관련 집단의 유전적 기여와 폰토스-카스피 대초원Pontic-Caspian Steppe의 키메리아족 조상Cimmerian ancestry 흔적이 포함된다.

동서 유라시아 조상의 풍부한 상호작용은 고대 대초원 민족의 유전적 지형을 형성한 복잡한 역사적 이동, 문화 교류, 그리고 통혼 패턴을 암시한다.

그들의 DNA에서 관찰되는 다양성은 유목 사회의 역동적인 특성과 광대한 지리적 거리에 걸쳐 형성된 광범위한 상호작용 네트워크를 반영한다.

친족 관계망과 사회 조직

유전적 증거는 단순한 무덤 표식grave markers과 무덤 배열burial arrangements을 초월하는 복잡한 친족 관계 패턴을 보여준다.

분석 결과 매장된 사람들 사이에는 복잡한 2촌 및 3촌 관계망이 존재했으며, 이는 사카 공동체를 하나로 묶는 정교한 사회적 유대감을 시사한다.

놀랍게도, 현장에서 함께 매장된 1촌 친척은 발견되지 않았지만, 더 먼 유전적 관계의 존재는 사망 시 직계 가족을 의도적으로 분리하면서도 더 광범위한 친족 관계를 유지했을 수 있는 치밀하게 조직된 사회 구조를 시사한다.

분석된 모든 남성이 동일한 하플로그룹haplogroup을 공유하는 남성 Y 염색체 계통에서 관찰된 동질성은 여성 미토콘드리아 DNA에서 발견되는 눈에 띄는 다양성과 극명한 대조를 이룬다.

이러한 패턴은 남성이 조상의 집 근처에 머무르는 반면 여성은 결혼 및 기타 사회적 관계를 통해 공동체를 이동한 부계patrilineal 거주 문화와 완벽하게 일치한다.

여성의 이러한 이동성은 사카 사회의 부계 중심적 핵심patrilineal core을 유지하면서 새로운 유전적 계통과 문화적 관습을 도입하여 더 광범위한 유전적 및 사회적 구조를 형성하는 데 기여했다.

증거는 "능력주의적 부계 계승meritocratic patrilineal succession"이라고 부를 수 있는 시스템을 시사하는데, 이 시스템에서는 엄격한 부계 상속strict father-to-son inheritance이 아닌 대가족 네트워크extended family networks를 통해 리더십과 권위가 흐를 수 있었다.

권력 계승에 대한 이러한 유연한 접근 방식은 성별에 관계없이 뛰어난 개인을 인정할 수 있게 했고, 유능한 여성들이 공동체 내에서 권위와 영향력을 행사할 수 있는 길을 열어주었다.

문화 유산과 역사적 의의

보즈-바르막 묘지는 단순히 고대 엘리트들의 안식처가 아니라, 전통과 적응의 균형을 성공적으로 이룬 정교한 유목 문명을 들여다볼 수 있는 놀라운 창구 역할을 한다.

이 유적은 복잡한 사회 계층, 광범위한 무역망, 예술적 성취, 그리고 리더십과 성 역할에 대한 유연한 접근 방식을 특징으로 하는 사회를 보여준다.

쿠르간의 세심한 배치, 풍부한 부장품, 그리고 매장된 사람들의 유전적 다양성은 모두 대초원 전통에 깊이 뿌리내리면서도 외부의 영향과 혁신에 매우 개방적이었던 문화를 보여준다.

보즈-바르막 유적 발견을 통해 드러난 사카 문화는 중앙 유라시아 역사 지리학에서 중요한 장을 차지한다.

이들의 이야기는 고대 세계를 특징짓는 이주, 문화 교류, 그리고 사회적 적응의 역동적인 상호작용을 보여준다.

고고학적 증거와 유전자 분석을 통합함으로써, 우리는 이 유목 민족이 유라시아 대륙 전역에 걸쳐 복잡한 사회 구조와 광범위한 상호 작용 네트워크를 유지하면서 어떻게 환경의 어려움을 헤쳐나갔는지에 대한 전례 없는 통찰력을 얻게 된다.

***

이 아티클 출처는 아래라, 나아가 아직 동료 평가를 받지 아니한 상태에서 bioRxiv에 올랐나 보다.

전반하는 수준을 보니 연구가 상당히 치밀하다는 느낌을 받는다.

이 엄청난 연구성과가 고작 인골 12개체에서 뽑아낸 dna에 기반한다는 사실이 놀랍지 않은가?

https://community.mytrueancestry.com/unraveling-iron-age-saka-culture-through-ancient-dna-analysis-in-kyrgyzstan/?fbclid=IwY2xjawN_zihleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETFzaFdUZVNKemNpYkdHUXZic3J0YwZhcHBfaWQQMjIyMDM5MTc4ODIwMDg5MgABHrwMGe2Me2LDW2OlCQSTOeKplqamKYRGkwJbKGZB7tivXOsP4Pvtef3d8MJD_aem_OE7VDlCAn98CJC5j5dPt0w

Iron Age Saka Genetics: Ancient DNA Insights in Kyrgyzstan

"Iron Age Saka culture in Kyrgyzstan unraveled through ancient DNA: Discover a genetic tapestry revealing gender roles, ancestry & archaeology."

community.mytrueancestry.com

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.03.686206v1.full

***

앞 아티클을 보면 어느 기관 누가 주도한 연구인지를 알 수 없는데, 아래 관련 기사를 보면 구런 궁금증이 드러난다. 다음 긴 아티클을 지금 다 번역할 순 없고 필요한 대목을 보면

Kyrgyz — Heirs of the Saka-Scythian Civilization: A Genetic Study by the University of Vienna (2025)

An international team of researchers from the University of Vienna, Western Michigan University, and the American University of Central Asia in Bishkek has confirmed the Scytho-Saka origins of the Kyrgyz people in their scientific study titled “Genetic Insights into the Saka Culture of the Iron Age: Ancient DNA Analysis from the Boz-Barmak Burial Site, Kyrgyzstan.”

비엔나 대학교, 웨스턴 미시간 대학교, 비슈케크 소재 미국 중앙아시아 대학교 국제 연구팀이 "철기 시대 사카 문화에 대한 유전적 통찰: 키르기스스탄 보즈-바르막 매장지 고대 DNA 분석"이라는 제목의 과학 연구를 통해 키르기스족이 스키타이-사카에 기원했음을 확인했다.

"철기 시대의 유목 문화는 유라시아 인구의 유전적, 문화적 지형을 형성하는 데 중요한 역할을 했다. 그러나 중요한 지리적 위치에도 불구하고 중앙 유라시아 지역은 인류의 고대 DNA 연구에서 여전히 제대로 다루어지지 않고 있다."

저자들은 사카 목축민(기원전 4~2세기)과 관련된 키르기스스탄 보즈-바르막 매장지에서 발견된 12명 개인 유전체 분석을 통해 이러한 간극을 메웠다. 그중 9명은 낮은 유전체 커버리지를 보였다.

“The nomadic cultures of the Iron Age played an important role in shaping the genetic and cultural landscape of Eurasian populations. Yet despite its key geographical location, the Central Eurasian region remains underrepresented in ancient DNA studies of humans.

We address this gap through genomic analysis of 12 individuals from the Boz-Barmak burial site in Kyrgyzstan associated with Saka pastoralists (4th-2nd centuries BCE), 9 of which yielded low-coverage genomes.

Genetic clustering analysis placed these individuals within the genetic variation of ancient and modern Central Eurasian and Siberian populations.

We found no evidence of first-degree relatives in a kinship analysis, however a network of second- and third-degree relationships seems to be present.

Notably, all male individuals share the same Y-chromosomal haplotype, common in present-day Kyrgyz and Tajik groups, while mitochondrial DNA showed comparably high diversity, with distinct haplogroups observed across the analysed individuals.

These findings are in line with archaeological and ethnographic evidence of patrilocality in Early Iron Age Saka, where male lineages remained stable across generations, while female mobility contributed to genetic diversity.

Our study complements our understanding of the interplay between kinship, social organization and population history in nomadic cultures.

In the Eurasian Steppe, a dynamic population history with continental-scale migration events took place, with Central Eurasia playing a crucial role as a crossroads of continents, as demonstrated by the westward expansion of pastoralist groups from the Altai region around 5,000 years ago.

These migrations into Europe and South Asia are believed to have spread some of the Indo European languages, fundamentally reshaping the linguistic and genetic landscape of a large part of the world.

The Iron Age (IA) (ca. 1000 BCE – 500 CE) marks an important period in Eurasian history, when nomadic horse-riding cultures emerged as powerful forces that reshaped the genetic and cultural landscape of populations across the continent.

Among these groups, the Saka peoples, closely associated with the Scythians, stood out as one of the most prominent IA cultures.

Their presence across the vast Central Eurasian Steppe, inhabiting various ecological and climatic conditions, led to the development of distinct economic systems.

This resulted in the profound complexity of the Saka confederation.

It is believed that Saka were a political union of different tribes united by military discipline and at the core of their society stood the kin, an extended unit composed of several families.

These kin groups could hold territories, with land regarded as communal property controlled by kin leaders.

Some kins were noble houses. Among nomads, the principle of kin-based inheritance of supreme power was rooted in the idea that authority belonged to the entire ruling lineage.

According to the genetic evidence, the Saka people likely originated in the Central Eurasian Steppe and were descendants of Late Bronze Age (BA) steppe herders admixed with hunter-gatherers from neighboring regions.

The differences in the sources and proportions of hunter-gatherer ancestry among the people associated to the Saka culture show that groups of the confederation arose from separate local populations in different places.

Notably, in some populations, such as Saka of present-day Kyrgyzstan, Iranian Neolithic ancestry is also present, suggesting interaction with the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), a sophisticated sedentary civilization of farmers in present-day Turkmenistan.

While these studies provided insights into the origins of Saka, their genetic substructure and kinship practices remain poorly understood.

The iconic and often massive monuments of the steppe, kurgans, were widespread from the northern Black Sea in the west to the region of Siberia and northern China in the east, including Central Eurasia.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the oldest dated Scythian kurgans are from the 9th century BC found in present-day Tyva republic, southern Siberia.

The size of the Scythian kurgans and graved artifacts, including various weapons, jewelry and pottery, appear to be correlated with the social status and degree of nobility of the person buried.

For example, at the Besshatyr kurgan complex in Kazakhstan, the mounds of Saka military leaders reached up to 105 meters in diameter and 17 meters in height.

In Scythian-related cultures, including Saka, the burials were arranged in straight-line sequences, or meridional chains, that varied in size and complexity, reflecting the considerable, large-scale communal effort invested in their construction and the existence of social hierarchy.

The burials of armed warrior Saka women suggest that, despite the prevailing patriarchal system, women could hold important positions within the community, could have been free to choose their husbands and, equally with men, took part in military activities.

Nevertheless, the fine-scale social structure of the Saka still remains a subject of debate. To address questions on genetic diversity and social structure of the Sakas, here we focus on the Boz-Barmak burial ground in present-day Kyrgyzstan.

Our approach combines archaeological analysis of burial structures and artifacts with ancient DNA analysis, to enhance our understanding of Saka culture.

Results: Burial ground archaeological context

In 2022, as a result of rescue excavations, the Boz-Barmak burial ground was excavated during the construction of the Balykchi–Ak-Olon railroad.

The Boz-Barmak burials are located in the Boz- Barmak mountains, approximately 4 km southeast of Balykchi town, along the southwestern shore of Issyk-Kul Lake.

The burial ground can be dated over a period between the 4th-2nd centuries BC, which chronologically fits within the Iron Age.

The site consists of 14 single-individual burials aligned in a chain from north to south oriented by head to western sector, though some are positioned outside the main sequence.

The burial mounds have diameters from 7 up to 10–14 meters and reach a height of about 1 meter, indicating that they belonged to the local elite.

The burials exhibit a sophisticated construction. The burial pits were covered with timber placed transversely, followed by a layer of shrubs.

This structure was then secured and surrounded by clay blocks, which were cut from nearby sources to form the base of the mound.

The clay base was reinforced with layers of rock. Additionally, stone rings were placed around the perimeter of the burials to stabilize the mound.

Genetics:

The mtDNA analysis resulted in assigning each individual a different haplogroup, all of which are in line with broadly Eurasian ancestry (e.g. Yakut C4a, Uzbek HV6, Chinese K2a, Eastern Europe U2e).

The male individuals were all assigned to one Y chromosome haplogroup, R1a1a1b2, which is commonly found in present-day Kyrgyz and Tajik individuals.

(The haplogroup R1a-Z93 predominates in the gene pool of the Tian Shan Kyrgyz, reaching record levels—over 60%—which ranks among the highest frequencies in the world.)

In this study, we presented genetic data from 12 Early Iron Age pastoralists from the Boz-Barmak burial site in present-day Kyrgyzstan, with 9 low-coverage whole genomes (on average 0.7-fold coverage).

The Boz-Barmak individuals were shown to be of Central Eurasian ancestry and are best modeled as a mixture between EIA Scythian-related groups, such as the Cimmerians and Sargat culture, and an Iranian-related source.

This component includes ancestry from Neolithic pastoralists from South Central Asia, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, and Mesolithic Western Eurasian hunter-gatherers from Bulgaria.

These results corroborate historical hypotheses suggesting a cultural connection between the northern steppe populations and southern civilizations.

Our findings support the genetic heterogeneity of the Saka by demonstrating several possible primary ancestry source populations and various admixture proportions among the Boz-Barmak individuals.

By integrating ancient DNA analysis results with archaeological data, we gained insights into the social structure and kinship practices of Early Iron Age Saka people at Boz-Barmak.

The genetic evidence revealed that the burial ground was organized around a network of second-, third- and higher-degree genetic relationships.

Crucially, the presence of diverse ancestral backgrounds within this network suggests that the social concept of kinship could have been flexible enough to tie individuals from varied lineages into a single kin group or extended family.

The group might have been local elite or individuals closely associated with them as the burial chain consists of large and complex kurgans with valuable material artifacts.

Archaeological evidence indicates that such chains were carefully planned, a pattern also evident at Boz Barmak, where the entire burial chain appears to have designated places for each individual.

The Boz-Barmak burial ground is represented by six large kurgans (5, 8, 10, 11, 12 and 13), surrounded by smaller, less complex burials.

One plausible interpretation is that the chain began with K10.1 and 10.2 as a couple, given both individuals buried were over 55 years old.

Power may have then passed to K8 (female), followed by K5 (male), later to K13 (female) and finally to K12 and 11 (both females).

This proposed sequence, together with the evidence of a single predominant Y chromosome lineage, could suggest that authority was transmitted through the paternal lineage, regardless of whether the successor was male or female.

We therefore hypothesize that the kinship relationships observed here might be concordant with a system of succession where power may have passed on not strictly from father to son, but to other relatives across the extended family, who were seen as the most influential at the time.

Women in power could have included sisters, nieces, granddaughters, great-granddaughters, first cousins etc. of male individuals representing the local kinship.

Such a speculative system of “Meritocratic Patrilineal Succession”, where meritocracy is sex or gender-neutral, finds parallels in ethnographic models of non-linear, or collateral, succession known in other pastoralist Inner Asian societies and is potentially supported by the rich burials of other Scythian-Saka women, suggesting female authority was a feature of these cultures.

In conclusion, our analyses corroborate that Early Iron Age Saka people formed through extensive admixture between preceding populations from the Eurasian Steppe and various neighboring regions.

The high diversity in mtDNA haplogroups and the predominance of a single Y chromosome lineage found in the Boz-Barmak individuals might reflect patrilocal practices.

Findings from other Scythian groups and broader Eurasian steppe populations have been interpreted to show a similar pattern, leading to the hypothesis that the males may have remained within their natal groups, while females moved between communities.

Taken together, our findings are in line with the suggestion that transmission of leadership among the Saka at Boz-Barmak mayhave had a complex nature, pointing to a sophisticated and adaptable sociopolitical organization.”

“Genetic insights into Iron Age Saka culture: Ancient DNA analysis of the Boz-Barmak burial ground, Kyrgyzstan”

Authors:

Aigerim Rymbekova, Pere Gelabert, Alejandro Llanos-Lizcano, Kaaviya Balakrishnan, Michelle Hämmerle, Olivia Cheronet, Aida Abdykanova, Keldibek Kasymkulov, Michelle Hrivnyak, Jacqueline T. Eng, Ron Pinhasi, Martin Kuhlwilm

Institutions:

Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Vienna, Austria

Human Evolution and Archaeological Sciences (HEAS), University of Vienna, Austria

Department of Anthropology, American University of Central Asia, Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic

Jusup Balasagyn Kyrgyz National University, Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic

Institute for Intercultural and Anthropological Studies, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, USA

Department of Biological Sciences, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, USA

Link: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.03.686206v1

'NEWS & THESIS' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 4,500년 전 프랑스 무덤이 현대 유럽인의 유목민 유산을 밝히다 (0) | 2025.11.12 |

|---|---|

| 네안데르탈인 DNA가 얼굴 형성 과정 설명에 도움을 주다 (0) | 2025.11.11 |

| 무주군 무풍면, 호남 땅의 경상도 : 성현석성의 경우 (0) | 2025.11.11 |

| 하와이 야생블루베리, 6,000㎞ 날아 일본에서 왔다 (0) | 2025.11.11 |

| 단순하게만 보이는 스페인 선사 도기들에 복잡한 사회 구조가 있다 (0) | 2025.11.11 |

댓글